The Jam secured 4 number singles ‘Going Underground’, ‘Start’, ‘A Town Called Malice’ and ‘Beat Surrender’.

As a solo artist Paul Weller has had 4 number solo albums: Stanley Road in 1995, Illumination in 2002, 22 Dreams in 2008, and Sonik Kicks in 2012.

People always ask me how I write. No idea. It’s just something in me. It’s the most insurmountable thing until you’re doing it and then it seems just like walking or breathing.

You get lazier the older you get. The days of waking and thinking, ‘I’ve got to write this down’ are over – I can’t be bothered. I think, ‘I’ll wait till the morning and it’ll come back.’ Or not.

I’ve always plundered the Beatles songbook. Even after all these years, there are chord changes which come direct from the Fabs.

Some are autobiographical, but very few. I don’t live an interesting enough life to write about it all the time.

I don’t care about those records that just talk about themselves. That whole singer-songwriter thing from the 1970s – give it a break, cheer up, d’you know what I mean?

I’m still in love with trying to condense a grand idea into a three-and-a-half-minute pop song. It’s special when you pull it off. It’s a product of me growing up in the 1960s. When you think of all the twists and changes in Good Vibrations in just over three minutes, it’s incredible.

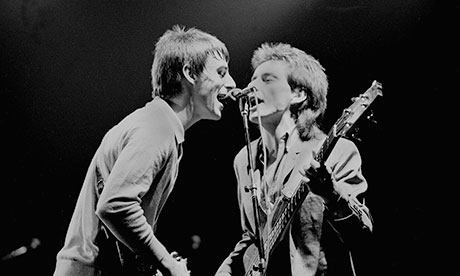

Paul Weller at Abbey Road by Chris Metzler

“Down in the Tube Station at Midnight” revealed your sophistication and depth as a songwriter. Can you describe the evolution of that song and your changing ability to hone in on the small and the particular?

That started as a long prose-poem thing, like a short story in a way. It came from my insecurity and paranoia at being in London. I didn’t have any music for it. I was in two minds whether to do it. I was coaxed and talked into it by Vic Smith, our producer at the time. He was saying: “This is really good, you should try and set it to music.” The attention to the details is part of the person I am anyway, but it’s also bound up in the mod ethos which is predominantly all about attention to detail. We were talking about English songwriters: it’s picking up on the mundane, the everyday things and putting them, into a different setting, the very, very ordinary feelings, emotions or details that, once in song, you hear them in a different way. Without something too poncey or pretentious I was thinking about pop artists as well, where they took the everyday objects and made them into art. I don’t think it’s that dissimilar.

What was the appeal in chronicling the mundane?

It’s a very English thing, the way we all like to moan about the weather or we like a cup of tea or a particular fucking biscuit and all that nonsense, but it’s us. It’s our identity, isn’t it?

“Saturday Kids” and “That’s Entertainment!” are songs that touch people’s experiences very deeply but with an apparent simplicity. Was that difficult to achieve?

It was easy for me because that’s just who I was. I was a very simple person; there isn’t any great intellect behind it. It was the simplicity that people connected with: a 20-year-old kid or young man writing how I saw and felt it and connecting with other 20-year-old young people. I didn’t have to sit down and deliberate too much on it, put it that way.

As in “A Town Called Malice”, which for such an upbeat song drops to a minor chord on the verse after the introduction. The flirtation between the major and minor chords is very effective.

It is effective, yeah. That’s just born out of me growing up on the Beatles and Motown, because they use all those kind of mechanisms. It’s part of your tools of the trade.

Leave A Comment