Jarvis v Jacko: Why the Pulp singer’s stage invasion at The Brits remains a defining Britpop moment

Leaping on stage to mock Michael Jackson’s ‘messianic’ performance of ‘Earth Song’ saw Cocker taken to a police station and excited a tabloid frenzy. Looking back it seems more significant than Blur v Oasis, says Ed Power

Running a gauntlet of child and adult extras dressed as stylised beggars, Jarvis Cocker of indie band Pulp had just gatecrashed Jackson’s 1996 Brit Awards performance. In a display of irreverence, Cocker waggled his rear at the crowd, pretending to break wind. Shortly afterwards he was gone while Jackson sang on. Nobody in the room fully appreciated that they had just witnessed one of Britpop’s defining moments.

But what had possessed the thoughtful and often tortured Cocker to rush the stage so cheekily? His answer was that he was protesting against Jackson’s messiah complex.

Nobody could deny Jackson’s bit at the Brits was over the top. But that was the point of “Earth Song”, wasn’t it? Originally titled “What About Us?”, the track had come to him, essentially fully formed, several years earlier while he was staying at the Hotel Imperial in Vienna.

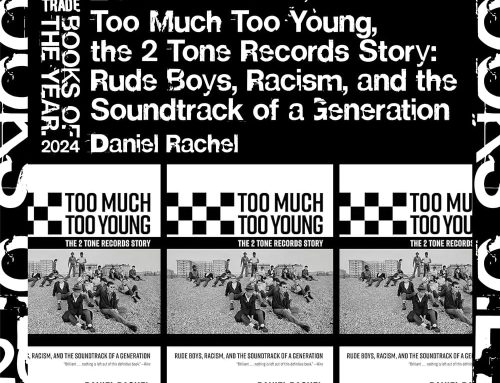

“It was an innocuous and fun thing really, to go on and wave your buttocks while you’ve still got your trousers on,” says Daniel Rachel, author of Don’t Look Back in Anger: The Rise and Fall of Cool Britannia, Told by Those Who Were There. “It was to do something and to stand by your principles.

“It’s all well and good being an armchair critic, even if you are at an awards ceremony. Just whingeing about it. He made a stand, just in his own mind. You wouldn’t have the foresight, in a split second, [that] this was going to become a national story and become a pinnacle point of the decade. That’s beyond what his actions were for or why he did them.”

A quarter century on, in light of the many abuse accusations made against Jackson, it’s obviously unnerving to see the self-proclaimed King of Pop flanked by adoring children. But in the immediate aftermath of the Brits sympathies were with the American. Though he finished “Earth Song” and humbly accepted his award for “Artist of a Generation”, the next morning Jackson put out a statement condemning Cocker: “I’m sickened, saddened, shocked, upset, cheated and angry, but immensely proud that the cast remained professional and the show went on.” Jackson’s camp also accused Cocker of “harming” three children.

Cocker would quickly clear his name. David Bowie, at the Brits to receive a Lifetime Achievement award from Tony Blair, had recorded his own footage of “Earth Song”: it clearly showed the Pulp frontman walking across the stage without coming into contact with any children. And yet, even with his innocence confirmed, the blitz of publicity that ensued was hugely unsettling for the sensitive and introspective Cocker.

“In the UK, suddenly, I was crazily recognised, and I couldn’t go out any more. It tipped me into a level of celebrity I couldn’t ever have known existed and wasn’t equipped for. It had a massive, generally detrimental effect on my mental health,” he told The New York Times last July.

Even without Jarvis and Jacko, the 1996 Brits were always destined to go down in history. They followed on from the summer of Britpop, in which Blur and Oasis had staged their ding-dong chart battle. Tony Blair, the 42-year-old leader of the opposition, was to attend the ceremony, where he would proclaim his devotion to David Bowie. Footballers Stan Collymore and Robbie Fowler were in the room, as were actors and comedians such as Martin Clunes, Neil Morrissey and Bob Mortimer. For a few hours, Earls Court was the beating heart of British celebrity.

‘Jarvis is innocent’ – Cocker was saved by footage recorded by David Bowie’s team

If anything, Cocker’s stage invasion was regarded by eyewitnesses as low in the pecking order of controversies. Pride of place, it was felt, went to Noel Gallagher of Oasis who, upon receiving the gong for Best British Group from Pete Townshend, plunged into an impromptu party political broadcast. “There are seven people in this room who are giving a little bit of hope to young people in this country… That is [sic] me, our kid, [Oasis members] Bonehead, Guigs, Alan White, [Creation Records boss] Alan McGee and Tony Blair.”

Twenty minutes later, it was the turn of Blair himself to shine as he presented the Lifetime Achievement award to Bowie, who was sporting his Outside-era ginger beard and an earring that declared “SEX”. In the wings, Blair’s press advisor Alastair Campbell was biting his knuckles, praying he and his boss got through the evening without any rock stars taking a swipe at New Labour from the podium.

The devastating pot shot when it came, however, was directed not at Tony Blair but at poor Michael Hutchence of INXS. He was looking characteristically dapper as he strode out to present Oasis with yet another award, this time for Best Video. Then Noel Gallagher grabbed the mic and said “Has-beens shouldn’t be presenting awards to gonna-bes”.

Hutchence, who died by suicide 18 months later, was reportedly crestfallen. Still he would seemingly have his revenge recording the single “Elegantly Wasted”. Doing backing vocals, he apparently sang the line “I am Elegantly Wasted” as “I am Better than Oasis.”

“Noel Gallagher making that great statement: the seven most important people in the room and Tony Blair’s the man. That would have been the headline news, and less Jarvis,” says Daniel Rachel.

He suggests that but for those two moments, the Brits that year would have been just another chapter in everyday Nineties music biz hedonism. Indeed, many of the journalists sent to cover the awards missed the Jarvis stage invasion because they were too busy making a beeline for the bar.

“In terms of all the revelry, that was the Brits, wasn’t it?” says Rachel. “A cocaine festival.”

But if few in the room grasped the significance of Jarvis’s stage invasion, backstage the Pulp singer was soon made aware he was in hot water. With Jackson’s lawyers claiming Cocker had assaulted several of the children, police corralled the indie star in his dressing room and questioned him for two hours.

He was next led to a police station, where Jackson’s legal team had already assembled. Bob Mortimer, a qualified solicitor who had worked at Southwark Council, had dashed from Earls Court to plead on Cocker’s behalf and offer moral support to the bruised Pulp star. Cocker was finally released, without charge, at 3am.

A blink-and-you’ve-missed-it incident had now taken on a life of its own. “He’s Off His Cocker” went The Sun. “Jacko’s Pulp Friction” proclaimed the Daily Express.

Suddenly everyone in Britain knew the name “Jarvis Cocker”. The NME was selling “Jarvis Is Innocent” T-shirts. That Thursday, it sent a reporter to Pulp’s Birmingham NEC gig to canvass the opinion of his bandmates and of the public. It ran as a cover story headlined, “Wanna Be Startin’ Something: Jarvis, Jacko and the True Story of the Brits”.

“I actually like Michael Jackson, I like some of his songs and I thought the last album was alright,” Pulp bassist Steve Mackey told the paper. “But Monday night was a case of the emperor’s new clothes; someone had to stick a pin into the balloon and burst it, so everyone could say that he was s**t. And that’s what Jarvis did.”

“I was encouraging him” added keyboardist Candida Doyle. “But you can’t make Jarvis do anything; he only ever does what he wants to do. The truth will come out – the papers get closer to the truth every day, you’ll all find out soon enough.”

Jarvis’s unlikely saviour: the late David Bowie

By the time her remarks made it to print, the Bowie footage had been released, confirming Cocker had not assaulted any children. Charges were dropped. And yet the following evening the singer came across shaken and defensive when appearing on Chris Evans’s TFI Friday. Evans, never more punchable than at that moment, clearly found the entire affair hilarious. Not so the Pulp man, who batted away the cheeky banter with a pronounced solemnity.

“The horrible bit of it [was when] they arrested me. ‘Oh, you ran onto that stage and assaulted some kids.’ I couldn’t believe they were saying that at first,” he told Evans, who had actually hosted the Brits that fateful Monday. “They carted me off to the police station. It wasn’t so much of a joke then.”

In Britain at least, sympathies had swung definitively towards Jarvis. Still, not everyone accepted his argument that Jackson’s “messiah” routine merited intervention.

“He [Jackson] was expecting to be the new King and kind of expecting his bigness to be interpreted as holiness. But, as I will never tire of saying, this is the fundamental point and purpose of art; to exceed oneself, to make claims towards God,” opined music writer Marcello Carlin in an essay in the 2009 collection of think-pieces about Jackson, The Resistible Demise of Michael Jackson.

“What was the more egocentric – his 1996 Brit awards performance of ‘Earth Song’ or Jarvis Cocker’s interruption of it? … It’s a complex and passionate protest song. Cocker’s bum, in contrast, was reductionist, petty … And it is significant that Cocker’s career began to parachute slowly towards nothingness from this point.”

Pulp’s popularity indeed waned, though Cocker seemed at peace with the spotlight turning elsewhere. He exorcised his A-lister demons on Pulp’s next album, 1998’s This Is Hardcore. The record was interpreted as a shriek into the void by an artist held captive by fame and desperate to break free.

“Pulp were always the outsiders,” says Daniel Rachel. “Jarvis would talk about people on the sides of society who aren’t normally given a voice. He’s a representative of these people. In terms of Jarvis Cocker as national hero or having national status, it’s this moment [the Jackson stage invasion] that changes the perception of Jarvis Cocker in the eye of the great British public. I don’t think he revelled with delight. I think he revelled quietly in upsetting the mainstream.”

The paperback edition of Daniel Rachel’s ‘Don’t Look Back in Anger: The Rise and Fall of Cool Britannia, Told by Those Who Were There’ is published on 18 March

Leave A Comment