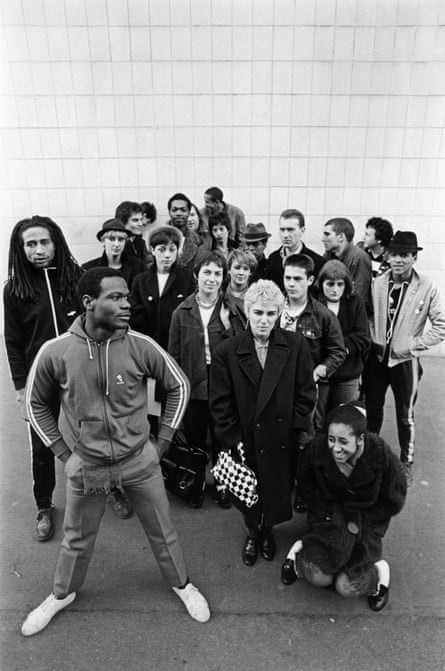

‘Richard Branson was shrieking: has anyone signed them yet?’ The invasion of all-female ska band the Bodysnatchers

In an extract from a new book documenting the 2 Tone ska scene of late 70s and early 80s Britain, members of its key girl group relive their bright, brief and often brutal career

‘I remember being 15, 16, 17 and being so tremendously bored,” says Nicky Summers, whose all-female London-based band the Bodysnatchers would soon become a cornerstone of the 2 Tone ska scene of the late 1970s and early 1980s. “Top of the Pops had gone stale. A whole generation was waiting for something. There were no jobs. We had electricity blackouts, garbage strikes. Something had to happen.”

Inspired by the Slits, and the fusion of fashion and energy wrapped up in the Specials’ live shows, Nicky placed a series of adverts in the music press in May and July 1979. “All I got was three months of dirty phone calls,” she says. “I thought a lot of girls would want to do it, but it didn’t seem that way.” After what seemed an interminable period of waiting, Jane Summers, a drummer and part-time lifeguard, responded. “Jane assured me she had a drum kit, but I never saw it for six months,” laughs Nicky. Next, they met Stella Barker and Sarah-Jane Owen; trembling with nerves, Penny Leyton picked up the phone and organised an audition. “They had a piano in the rehearsal room, and I played Scott Joplin!”

Now a five-piece, the teenagers extended their search for a brass player. Miranda Joyce suddenly appeared, pushed into the rehearsal room by a boy who practised in the adjacent room, who announced, “This is my sister.” Asked if she could play an instrument, Miranda replied, “No – not yet.”

Six down. One to go. But where to find a singer? After work, Nicky would often go and watch bands in London with her friend Shane MacGowan (later of the Pogues). One night, she saw him talking to a girl of mixed heritage. Intrigued by her striking image, she asked for an introduction. “I went, ‘Yeah! I sing in the bath’,” says Rhoda Dakar. “I thought if Shane knows her, she must be alright.”

Sharing her vision to be a female version of the Specials, Nicky laid it on the line from the get-go: “We’re going to go places. Everybody’s got to focus. We’re not going to muck about. This isn’t a hobby.” Practising three nights a week on Royal College Street in a basement shared with Adam and the Ants and the Vibrators, Nicky says, “We weren’t very slick or professional musically, but that became our sound and reflected how we played.” Abundantly aware that 2 Tone was a British take on Jamaican music, Nicky says, “You couldn’t replicate black music or a Blue Beat record and do it justice. But you could do your contemporary take and put your input and life in it.”

Plugging a Dansette record player into a light socket, the girls studiously listened to ska and R&B records – Time is Tight, Monkey Spanner, 007 – to understand what made up the different elements of a song. Enjoying the naivety of it, Miranda says, “It held together on a thread. Had it been all guys I would never have gone for the audition. It’s terribly sexist I suppose, but I thought men would be better musicians or more judgmental. All the boys I grew up with who were getting into bands had been playing for years.”

Aged 20, Penny was the only group member with knowledge of music theory, but she told Smash Hits at the time: “A lot of girls seem to think that if they’re in a band they’ve got to prove themselves instrumentally, or have got to put across some heavy point about sexism or feminism, so that in the end there’s no fun in them at all and they end up downright boring”. Promoting a sense of fun, Sarah-Jane suggested calling the band Pussy Galore. Nicky was not amused. “It smacks of 70s sexism and dirty old men.” Rolling her eyes, Rhoda said, “Fuck off. If you want to call this band Pussy Galore, do it without me.” Rejecting Soft Cell and the Avengers, Stella suggested the Bodysnatchers, influenced by having recently seen the film Invasion of the Body Snatchers. “It was the name that everyone hated the least,” scoffs Rhoda.

Marching across the sticky carpet at the Windsor Castle, in a support slot for the Nips, the Bodysnatchers plugged in their instruments. “My hands froze for the first song and we kind of fell apart towards the end,” recalls Nicky. “We were ramshackle and chaotic but people loved it.” Insistent that they had played all the songs they knew, the crowd demanded the Bodysnatchers play them all again. “So we did that,” says Stella. “It was amazing!”

Ten days later the Bodysnatchers played a second show at the Windsor Castle, again supporting the Nips, with the added pressure of ska legends Neol Davies, Pauline Black and Jerry Dammers standing down the front and, says Nicky, “Richard Branson running around shrieking: has anyone signed them yet?” The band fielded offers from the likes of EMI, Stiff and Virgin; Jerry was offering a two-single deal with 2 Tone Records. The Bodysnatchers voted and unanimously elected 2 Tone. “It all happened in two weeks,” says Nicky. “To make a decision, find a lawyer, record a single to coincide with the Selecter tour, and do all that and be thinking, ‘Shit! Am I being ripped off?’ I was out of my depth.”

“A fucking joke,” says Rhoda of the legal document. Too young to care, Miranda says “there was very little analysis. It was just, ‘Whoa! Great!’, like we were on some amazing rollercoaster ride.”

Cut at CBS Studios, debut single Let’s Do Rock Steady was released on 7 March 1980, entered the Top 40, and the Bodysnatchers accepted an invitation to appear on Top of the Pops. The limousine driver sent to pick up Rhoda in Brixton discovered she was busy shopping. “I came back and the limo was outside my flat. My dad was going, ‘This poor man is waiting for you. Where have you been?’ I said, ‘Firstly, this poor man is early, and secondly, I’m paying for this poor man to sit here so don’t you worry.’”

Three weeks later, they made a second appearance on Top of the Pops, Let’s Do Rock Steady now at a healthier No 22 in the charts. Positioned at the lip of the stage facing the studio audience, Jane spun round on her drum stool and began conducting her dancing bandmates with her sticks. It would be the last time they would appear on the show, but for now, the Bodysnatchers exhibited all the signs of a bona fide pop act.

On tour in spring 1980 supporting the Selecter, Rhoda would run from one side of the stage to the other, imploring the crowd to dance. “She really held it together,” admires Miranda. “She was such a great front person and had a good rapport with the audience. No one was a great musician. We were learning and getting better the more we played. If things went wrong or we were out of time, Rhoda would say, ‘Oh, fucking hell! Come on, let’s do it again.’ Nothing fazed her. She rolled with it and carried all of us.”

The group once attempted Mule Jerk five times and still failed to move beyond the introduction. “We weren’t good enough,” Rhoda says. “There wasn’t any leap of imagination. If it hadn’t been for Penny, we wouldn’t have been able to write any songs. She was the one who could say, ‘We’re playing in this key. This is where you need to play … these are the notes.’ Nobody had a clue. It was a baptism of fire.” Adamant that they were a product of punk as much as ska, Nicky Summers argues, “It wasn’t the point to be a proficient musician. It was about getting your thoughts across or your attitude or your energy or your fury or whatever it was. That was a large feature of the Bodysnatchers.”

Men mocked the novelty of an all-woman group. “Whenever we did a soundcheck there was a lot of expectation that we would not be able to play our instruments,” continues Penny in despair. “Roadies on the side of the stage with their arms folded going, ‘This is going to be a laugh!’” Night by night, the Bodysnatchers stood by the side of the stage and studied the stagecraft of the Selecter, how they got from one song to the next, until “slowly and surely we got tight”, says Penny. “The lighting crews and roadies changed their tune and realised we weren’t just a bunch of girls to be laughed at.”

“By the end of the tour,” adds Sarah-Jane, “we were a different band.” The band got down to hard partying and innocent fun. “We were like school kids,” laughs Rhoda. “We all had water pistols and soaked journalists whose questions we didn’t like.” Physically exhausted, Penny says by the end of the tour she was throwing up. “I don’t think we ever went to bed before three in the morning. It was nuts.”

The party mood was abruptly silenced when a fight in the middle of the dancefloor in Guildford forced innocent fans to cower on the edges of the auditorium. “People would be dancing, then somebody would push somebody or want to get in front and then a fight would break out,” says Sarah-Jane. “It just seemed that is what men did on a Saturday night.” Miranda says stabbings were a common occurrence. “Many skinheads carried knives. It was nasty. National Front supporters would dance merrily to black-influenced music played by black musicians. I was too young and naive to make sense of it all. Nobody can.” Attributing their actions to “herd behaviour”, Penny says: “Part of 2 Tone was to educate the audience and say black people invented this music. You need to accept that the world is two tone. It was trying to make people aware of equality and to stop racism.”

At Friars Aylesbury, opposing gangs clashed on either side of a gaping hole in the audience. “You can’t play when people are fighting,” reasons Penny, “and sometimes it would be women,” she adds, bemused. In Middlesbrough, violence spilled onto the street when an angry mob smashed the windows of the Bodysnatchers’ van. Taking it upon themselves to challenge the inherent contradiction between supporting 2 Tone and having racist attitudes, members of the band questioned the agitators. “Yeah, but we like the music.” “What about Rhoda then?” one of the girls asked. “She’s alright,” came the response. “She’s a tart, ain’t she?”

Boldness of mind had taken the Bodysnatchers from blowing away the mystique surrounding rock’n’roll to courting the attention of the music business. But when amateurism mixed with professionalism, there was little give. A drummer who could not keep time proved too much. Writing in her diary after a show at Hastings Pier Pavilion, Penny Leyton noted, “Miranda and I discuss Jane with Rob Gambino [tour manager] who says she’s crap and band won’t last three months – band agree to get rid of her.” The following day, Nicky delivered the news and Jane graciously agreed to stay for the rest of the tour.

Never one to mince her words, Rhoda Dakar says that Jane was not only a “terrible drummer” but “a cow. She had a little plastic kit with a razor blade and a straw that she used to carry about with her. I just thought, you’re pathetic. I once asked Paul Cook [Sex Pistols] to try to teach her how to play reggae. He came to the rehearsal studio, but it was a pointless exercise. A band stands or falls by its drummer. When we had a decent drummer, suddenly the possibilities opened up.”

Never contractually signed to 2 Tone, the new drummer Judy Parsons’ first engagement was to promote a record she had not played on: their second single, Easy Life. The song addressed parity in working wages and society’s expectation for women to procreate. “The good thing about 20-year-olds writing songs,” says lyricist Rhoda, “is that their ideas are pure and unfettered with complications, like, ‘how the fuck are we going to achieve that then?’ It’s like saying, ‘Let’s go to the moon.’ There’s no notion of ‘we actually have to build the rocket’. At 20, I thought motherhood was a thing that dragged you down. It was doing what everyone else did. But with the genius of hindsight, I now know that it’s a very empowering role.”

But Easy Life failed to make an impact and talk of a Bodysnatchers album crashed. Only recently, Richard Branson had been desperate to sign the group, “offering the earth” according to Nicky, “but the rest of the band wouldn’t meet him. I met this woman in Notting Hill. She bought us pancakes and said Branson wanted to take us to Memphis with Aretha Franklin’s producer. Five people refused to play ball. I don’t know why? It was like, ‘Aaarrggh! How can you let that go?’” Adding to their woes, the Bodysnatchers were broke.

Mulling over their precarious status, Penny says, “We were a novelty and novelty sells: an all-girl group playing ska; people were seeing great profit potential in us. But the fairytale had come to an end.” By the autumn Rhoda concluded, “We’d sacked the manager. We didn’t have a deal and we didn’t have a plan.”

“Ugly”, “nasty” and “physical” are three words repeatedly used by band members when retelling the break-up of the Bodysnatchers. Four decades after the event, Penny singles out a key moment where she remembers Rhoda throttling guitarist Sarah-Jane. Then, locating her diary from 1980, she is shocked at what she reads: “Friday 10 October, Edinburgh Uni [Freshers’ Ball]. Rhoda upset because she had to get up at 4pm for soundcheck which she didn’t have until 5.30pm. Causes hysterical scene, shouts at SJ and Miranda, tries to strangle me … I decide definitely things can’t continue this way …”

“It was me!” screams Penny, stunned. “Obviously I put that out of my memory and transferred it to SJ.” On hearing this, Rhoda also cries out. “What! I had her by her throat? Nah! Penny was a fruit-loop. Somebody said something that really annoyed me, so I had a go at them. Then Simon, our roadie, jumped in the middle and started having a go at me. Then my brother jumped in and basically said, ‘You hurt my sister and I’ll kill you.’”

Penny receives a lot of criticism. “Opinionated,” says Nicky. “Difficult,” says Judy. “Irritating,” says Stella, adding, “I suspect Penny was goading Rhoda or contradicting her. I could see it was going to explode. It was awful to witness. Penny was difficult, but Rhoda and Nicky could be as well.”

For her part, Penny compares the dynamic within the band to a blossoming romantic relationship. “In the early stages people are on their best behaviour, but as you get to know each other you feel freer and resentments come out. It’s ironic, since the whole idea of 2 Tone was to put differences aside and come together to promote a better society, that we couldn’t overcome our own differences.”

While not wholly absolving herself of blame, Penny points to other factors that ultimately split the band. “Rhoda had meltdowns,” she says. “She would just sit in a chair and scream. There was a lot of pent-up frustration in her. She had problems with me and SJ. She felt that we were privileged middle-class white girls who didn’t understand how things were.”

The social differences are what make the group such a fascinating study. Nicky’s parents owned a market stall in Soho; Rhoda’s father grew up surrounded by servants and worked in the music business. “My parents behaved as if they lived in a big house,” she says. “I was brought up to think of myself as someone who could expect everything and anything. I didn’t have the psychological or cultural restrictions of being working class.” Sarah-Jane compares herself and Stella to Victoria Beckham. “We came from very well-educated backgrounds,” she says, “whereas Nicky and Jane were what I call street kids.”

Identifying a clear class divide, Rhoda postulates, “It was about: should we upset the neighbours or shouldn’t we? I slotted into the working-class ‘Let’s rock the boat.’ … They were all fucking ridiculously rich. Stella’s dad owned a plane … How they treated me was neither here nor there. It was where I wanted to be. I didn’t think any further ahead than getting on Top of the Pops. Once I’d done that, I didn’t really know what else to do. I kind of lost momentum. When they treated me badly or it was apparent that it wasn’t going to improve, I was gone.”

“The five of us wanted to evolve and not just play reggae,” says Stella. “2 Tone was coming to a natural conclusion. It couldn’t sustain itself. We wanted to expand our musical repertoire.” Rhoda dismisses such ambition deftly. “They wanted to be pop tarts,” she states. “All the 2 Tone bands used to scrap and squabble. Just because you’re in a band didn’t mean you got on with them personally. You were thrown together in this cramped goldfish bowl space. You let off all your steam on stage, came off and you have all this energy. Inevitably people are going to argue, they have a drink, and sometimes it’s all going to go horribly wrong.”

On Halloween night in 1980, the Bodysnatchers performed for the last time. It had been just 11 months since their debut at the Windsor Castle. Two hundred-plus gigs later, Penny says, “We were all mentally exhausted. It felt more like three years than 11 months. It had been super intense.” Playing a set consisting almost entirely of original songs, Record Mirror described the farewell appearance at the Music Machine as celebratory: “It’s quite obvious that most of the band are in the party mood. The Bodysnatchers certainly went out in a blaze of glory, buried under a sea of confetti, streamers, rubber string from a spray can, and Doc Martens, as the skinheads invaded the stage.”

“And that was the band over,” says Judy. Answering her own question – why did it end? – Miranda cuts to the quick: “Nicky left and Rhoda got wooed away to do stuff with the Specials. We then morphed into the Belle Stars” – who had big hits with Sign of the Times and Iko Iko – “so it didn’t feel like it was an end. We just adapted to the people leaving.” Rhoda sums up the experience with blunt analysis: “I’d played with the Specials. Then you come back to the Bodysnatchers and you think, ‘They’re so shit.’ It was a relief.”

Leave A Comment