The Walls Come Tumbling Down tapes

Interviews, outakes and extras from Walls Come Tumbling Down

All of these extracts were taped between 2015 and 2016 during the research for Walls Come Tumbling Down. I talked to over 100 people in this peroid and due to the extensive length of many of the conversations it was not possible to reproduce them all fully in print. What you have below are some of those edited highlights, many of which add fascinating insight to the book containing background information and themes that deserve to greater development.

This first selection was updated on 22 .9.16

LITTLE BOY SOLDIERS

Rock Against Racism. The Jam

DAVE WAKELING: I wrote a letter to the NME. I was real excited and then it turned out there were loads of letters that said more or less the same thing but I was pissed off because most of them hadn’t been there. Red’s letter was meant to suggest that Clapton wasn’t a true revolutionary but I never really understood what Marley’s song meant in the first place I shot the sheriff but I didn’t shoot the deputy. I’m not really into shooting people and I don’t know if it would make it any better if you didn’t shoot the deputy – you’d only killed one person, not two?

ROGER HUDDLE: The International Socialists had set up a Right to Work Campaign to link the growing unemployed with those still in work to fight for jobs. There was a march from London to Brighton and I was to organize a gig on the way down as a social event to bind the young marchers together. It was about four days’ notice or something ridiculous so I got hold of Red. He said, ‘Too little notice but what we really need is a ‘rock against racism’ because the National Front is getting strong.’ That was the first time we used the words.

WAYNE MINTER The London to Brighton march was led by John Deason who was the leader of the campaign. The SWP were asking us to keep lists of potential supporters and started to get people like the Right To Work Campaign organizers to come along and speak from the stage. They did about two or three times before we found out. I had an altercation with John on stage in Skegness. We were probably both a bit pissed. There was a bit of a struggle for the microphone and we both led the stage rapidly over the front. They were excitable events.

JOHN BAINE: Right to Work asked me if I’d do a gig on the back of a lorry. On the day of the demo I met Steven ‘Seething’ Wells who had written to me to tell me about his Molotov Comics fanzine and the developing ranting poetry scene in Bradford. The same day there was a Poetry Olympics event at the Young Vic Theatre which Michael Horovitz had organized. I said to Swells, ‘Let’s go along and crash it.’ We found Michael and he gave us five minutes each straight after Roger McGough and immediately before Paul Weller who was doing a spoken word set. I ran on stage and spat out ‘They Must Be Russians’ and ‘Russians In The DHSS.’ We ripped the place apart. After, Weller said to Swells, ‘Do you want to come and support the Jam at Hammersmith Odeon?’ Swells said to me, ‘You got me on at this. You’re coming too.’ Two weeks later we went to the Odeon and Paul’s dad, John Weller said, ‘You the poet?’ Swells said, ‘Yeah.’ John said, ‘Who’s the other cunt, then?’

SYD SHELTON: We approached the Jam for RAR but Paul was more aloof then and wasn’t that keen on getting involved. And they suspiciously played with a Union Jack draped across an amp on stage.

PAUL WELLER: That fucking NME interview we did:

The only reason the Union Jack was involved was ‘cos it looked great on stage. The colours. You’ve got all the black and white, very negative, and then you’ve got this flash of colour.[i] ‘I don’t see any point in going against your own country. If there’s such a thing in this world as democracy, then we’ve got it. All this change the world thing is becoming a bit too trendy. I realize that we’re not going to change anything unless it’s on a nationwide scale.

That was us just being young and naïve and following the advice of our PR man, who suggested that the Pistols were into anarchy and the Clash were left-wing, why don’t you be Conservative, to set yourselves apart? What a fucking stupid idea that was. But I was just an ignorant, green kid from a little suburban town, and I really didn’t have any views, apart from just the usual teenage thing. I was never an intellectual; people would ask me questions and I didn’t have a fucking clue.[ii] I was eighteen. It was our first big interview. I really wanted the trendies to hate us and I succeeded in that. It was a mistake, I know. But we’re prone to mistakes. Only the Clash weren’t prone to mistakes.’[iii] I wasn’t right wing. If that impression’s came across it wasn’t meant to, cos I’ve got no allegiance to any fucking party. The only reason the Union Jack was involved was ‘cos it looked great on stage. The colours. You’ve got all the black and white, very negative, and then you’ve got this flash of colour.[iv]

ROBERT HOWARD: Paul Weller was a weirdo from Woking who dressed up in mod clothes when everyone else had forgotten about them. All Mod Cons and Setting Sons really pricked my ears up to Paul’s lyrics. ‘Saturday’s Kids’ and ‘Private Hell’ hit me emotionally.

DOUG MORRIS: Reading Shelley on the back of Sound Affects was a big thing for me. It sounds trite because I went to a comprehensive school in Gravesend but it was those introductions to literature or going to find the original of ‘Big Bird’ after hearing it at a gig.

BERNIE WILCOX: Weller on Setting Sons wrote some absolutely fantastic tracks. It was originally an idea that he had for a concept album about three lads from council estates who go off to different parts of the armed forces, they come back and have a get together how are things in your little world? I hope they’re going well, and you are too. ‘Little Boy Soldiers’ sounds two songs put together was all about going out to fight for something that didn’t really mean anything and you were just cannon fodder. The final words were it says with a letter to your mum / Saying find enclosed one son – one medal and a note to say he won. It was very, very political and really set the scene for the Style Council and ‘Walls Come Tumbling Down’.

[i] and [iv] Melody Maker 20/01/79 interview with Harry Doherty

[ii] May 7 NME

[iii] Sounds 16/6/79

BERNIE RHODES KNOWS DONT ARGUE

The Specials.

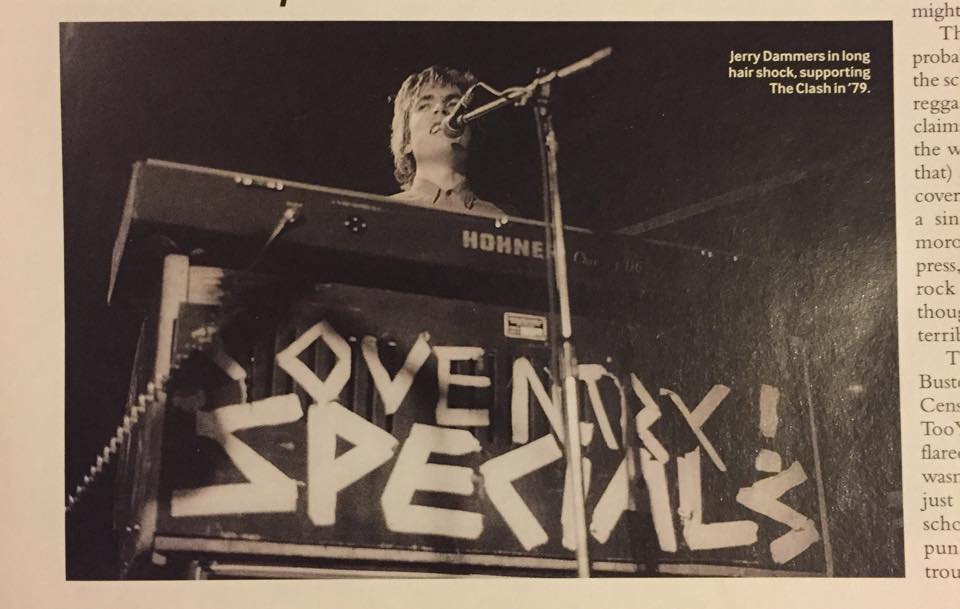

JERRY DAMMERS: I joined the Cissy Stone Band from Birmingham and we played funky soul all over the country in working men’s clubs and night clubs, but it was still all covers and they wouldn’t do any of my songs so I left when punk arrived. I also played with the black reggae band Hard Top 22 – most of whom later became the Selecter – for a while, who were a ray of hope in Coventry. I also played with a Teddy boy rock and roll band Ricky Nugent and the Loiterers and the Lane Travis Country Trio. But these were just covers bands; they weren’t very good or anything.

LYNVAL GOLDING: I met Jerry at a pub called the Pilot. I used to play there every Sunday night with the Ray King Soul Band earning good money. I run by Jerry’s house and he played me ideas on this great big old church split organ he had.

JERRY DAMMERS: Before we became the Specials everybody submitted a list suggesting names for the band. I’ll read some of them out to you: Double Agents; Copasetic; the Riots; the Rubbers; Blood Pressure; the Paragons, which was taken; the Sheiks; the Tongues; Beatitude; Attackers; Pleasurers, I liked that one. Lots of them sounded like Do-Wop bands. There were loads: the Invaders; the Competition; the Allstars; the Thundering Vibrations; Doctor Dick. Terry’s contribution was the funniest, the Six Petals. He also suggested the Knobbers, and also the Klan. The Blues – that was Horace; the M6; the Plumb-bobs! Terry’s contribution was funniest and typically sarcastic, the Six Petals – Sex Pistols, geddit? That led to me choosing ‘Specials’ partly because it sounded reggae-ish and partly because it sounded like saying ‘Sex Pistols’ when you were pissed.

RANKING ROGER: I went to see the Specials at Cannon Hill Park. The walls got damaged and there was a stage invasion. I was just about to grab the mic and do my likkel three lines and they stopped. ‘Gangsters’ wasn’t in the charts yet but it was being played at the clubs and everybody loved it; especially the heavy bass line.

HORACE PANTER: We did the Lark in the Park with Steel Pulse and the stage got invaded which they weren’t happy about that. The Specials came to prominence in Jim Callaghan’s government. We did the Clash tour during the garbage strike. We were as much railing against Jim Callaghan as Margaret Thatcher.

JERRY DAMMERS: We had many adventures on the Clash tour: sleeping on the grass verge of a dual-carriageway in the van with the pouring rain beating on the roof in Scotland; being put in a freezing cold police cell in Liverpool after I had been arrested for walking down the street with a pint of beer in my hand from the venue; witnessing violence at the Crawley Sports Centre.

LYNVAL GOLDING: On the way to Scotland we had no money so we pitched the van by the side of the road and slept in it on top of the equipment. I used Silverton’s drum carpet as a blanket and the next morning dusted myself off from the dirt.

HORACE PANTER: Suicide were the support act and some skinheads jumped on stage while they were playing and thumped the singer, Alan Vega. He came backstage and hurled a chair, ‘I’m on the next fucking plane home.’

PAUL HEATON: Suicide got terrible treatment; just spit flying; and Alan Vega was soaked in it.

LYNVAL GOLDING: Bernie Rhodes started helping us out but he thought we weren’t ready for the big time yet so he sent us to France. The hotel that we stayed in the Damned had been in the week before and smashed the place up and the lady said we had to pay for the damage. We got into a big argument and they took my guitar. ‘Gangsters’ was written about that experience.

JERRY DAMMERS: The line they confiscate all your guitars was about when we went to Paris and the hotel thought all English punks were the same as the Damned and took our guitars to pay for the damage done by them. And then the gangster owner of the club went with a gun and got them back so we could play the gig.

HORACE PANTER: When we first pressed ‘Gangsters’ the bass was all over the record. You put the stylus on at the beginning and it was like Bernie Rhodes knows don’t argue and then slpphhgg and the needle slid across the record. Jerry put this piano on top of it and that’s why it’s got that tiny yet really heavy sound at the same time.

JOHN JENNINGS: ‘Gangsters’ was basically Prince Buster. They used to re-hash reggae music.

LYNVAL GOLDING: The British sound is much cleaner but for depth and body the Jamaican records have it. If you listen to ‘Gangsters’ you hear the real heavy sound system bottom end. The first time Jerry had it mastered the needle just kept jumping off. It wasn’t like your normal pop record which is just thin

JERRY DAMMERS: With ‘Gangsters’ I had the idea of the echo actually being different from the lead vocal, so I got Terry to double track the vocal in a slightly different voice and then delayed that instead. It gives a slightly disturbing feeling, but you can’t really work out why, unless you listen very carefully. I was devious!

SHERYL GARRATT: There was a family called the Fewtrells who were like the Birmingham Krays and they ran a lot of clubs. When I heard ‘Gangsters’ live it sounded like I dread to think what the Fewtrells will bring but actually it was future will bring.

JERRY DAMMERS: The original line was can’t fight corporation with con-tricks. And the guitar solo idea came from the Fry’s Turkish Delight advert

LYNVAL GOLDING: We were always jamming and the song developed through that. A lot of Specials come about through us jamming and then Jerry arranged it.

JOHN JENNINGS: We’d been on Top of the Pops doing ‘Babylon’s Burning’ and some of the Specials had come to our gigs. Suddenly, 2 Tone kicked off and we were in one room with about three four hundred people and the Bodysnatchers, the Selecter, and the Specials, were in the next room and they had about two thousand. I spoke to Terry Hall and he said, ‘Oh sorry,’ That’s way it was.

JERRY DAMMERS: I remember one funny incident at the height of our success. I was with John Hasler, who had originally been in Madness, and we were in a tube station on a busy Saturday night and this train happened to stop loaded with gravel. I said, ‘Come on, John,’ and we both jumped on board. It was going through all these stations with crowded platforms and I was just waving to everybody like the Queen as we went through. We ended up in this siding miles away and luckily came to halt before we died of hyperthermia.

JULIET DE VALERO WILLS: I made Jerry have a bath at Trigger once. He hadn’t washed for ages and I said, ‘Go and have a bath.’ He was like, ‘Aaarghh.’ I was like, ‘For fuck’s sake. Right, I’m going to go and run it for you and then you’ll get it in and feel a hundred per cent better.’ And he did.

KILL A COMMIE FOR MUMMY

Artists Against Aparthied. Free Nelson Mandela

COLIN BYRNE: When I was in the Student Movement one of our jobs was to expose the right wing crazies running the Federation of Conservative Students (FCS) some of whom were thoroughly unpleasant young racists who wore ‘Hang Mandela’ T-shirts.

PAUL HEATON: The student unions were full of Steve Biko and Nelson Mandela and FCS stuff. We did a gig at North Staffs Uni and some kid had a ‘Kill a Commie for Mummy’ and a ‘Hang Mandela’ badge on – yellow with black writing – and I had my coat on which was covered in miners badges and I lost my rag with him, ‘I’m a Commie are you going to kill me? Come on then?’ I prodded him and he ran off and got his President. I said, ‘Take him and take that jacket off him otherwise we’re pulling the gig.’ He turned his jacket inside out and I said, ‘That’s not good enough. He’s not wearing the jacket.’

KAREN WALTER: I grew up with stories of Steve Biko. You couldn’t believe that people could do things like that to each other. It was heartbreaking. My aunt married somebody who was white who had family in South Africa and that brought it to the fore. It was unjust how the majority of the country was treated worse than animals and you had a minority ruling. It’s like the Haile Selassie speech, ‘Until the colour of a man’s skin is of no more significance than the colour of his eyes.’

TINY FENNIMORE: I was talking to my first black friend and he said something about ‘apartheid’ and I didn’t know what the word meant. Later, I looked it up in the dictionary and it was one of those big moments where you think, ‘Christ, that can’t be true. That can’t really be happening.’

KEITH HARRIS: Most people wouldn’t have had any idea. I heard Gill Scott Heron’s ‘Johannesburg’ in the mid-Seventies thinking, ‘That’s amazing, somebody’s writing about South Africa,’ somebody actually knows what’s going on.’ And then the fact that Thatcher’s government came out and strongly supported apartheid helped to drive the idea, ‘We’ve got to do something about this.’

JUNIOR GISCOMBE: Gil Scott Heron’s records were the beginnings of, ‘Hold on a minute. Is this true? Let me find out.’ Go to a library. So you start to understand what’s going on in South Africa and the African National Congress (ANC) boycott. I hated the fact that Elton John, Queen and Cliff Richard all played Sun City and had so much mouth about racism. This was the year of Live Aid. I went to the BRIT Awards and the only people who were black were Tina Turner, me, Five Star and Prince. They started by saying that, ‘So-and-so is on holiday in sunny South Africa.’ ‘Pardon?’ I get up from the table and the record companies gone crazy. And the press say, ‘Junior walked out.’ They made things very difficult for me. I told London Records I didn’t want money from South Africa and instead used the money to open a little school for young mothers who were unable to get childcare but wanted to go to university and better themselves.

JERRY DAMMERS: I eventually went on to organise a completely peaceful gig on Clapham Common for Artists Against Apartheid which attracted about a quarter of a million people, and that led directly to the Mandela Wembley concerts which were broadcast to what has been estimated at hundreds of millions around the world.

RICHARD COLES: We played the gig and Boy George was there looking half dead.

ANGELA BARTON: I remember seeing Lenny Henry and Dawn French walking round the back holding hands and thinking, ‘Ooh, they look sweet.

LORNA GAYLE: My dressing room was right next to Sade and I was sharing with Princess. But I wanted to meet Boy George. My mate and I tried to get in to his dressing room and we saw him by his mirror putting this white stuff all over his face. We were going, ‘Oh my god. Look at him!’ And then he pushed opened the door and went, ‘Aaaarrrgghh.’ We just ran, man!

ROBERT ELMS: George was in the middle of his smack period and he clearly was very sick. His face looked like it was covered in flour.

PAUL HEATON: There were all these Boy George fans, ‘Is he there? Will you take a photo?’ They didn’t know who I was, so I said, ‘Go on then. Give us your camera.’ I went in and he was rolling round the floor absolutely off his head covered in paste – the next day it came out in the News of the World he was on heroin – I went click, click, click, and gave it back to this young thirteen year old. I wanted to tell her the truth because she’d been so rude to me, ‘There you are. There’s your Boy George.’ It was horrible. He was in a right state. I wanted to help him.

***

JERRY DAMMERS: I invited a few friends to sing along – Ranking Roger and Dave Wakeling from the Beat, Elvis Costello and Lynval (Golding) from the Specials.

RHODA DAKAR: Jerry had the hook Free Nelson Mandela but we were still trying to finalize the lyrics out in the hall before we performed it for the Channel 4 music series Play at Home. By the time we got into the studio Jerry had written the words but there were a couple of lines of mine in there. Pleaded the cause of the ANC is definitely mine because I remember thinking ‘Plead I Cause’ which was a reggae dub song. It’s like pleading a cause; ‘case’. After it was released as a single I called the head of the record company and said, ‘My name should be on this. So the second pressing had the credit Dammers/Dakar.

JERRY DAMMERS: I wrote all of ‘(Free) Nelson Mandela’ except that Rhoda contributed one line. It’s not a big deal but my memory is that I actually wrote pleaded the cause of the ANC and I couldn’t think of a rhyme and Rhoda added only one man in a large army which was the kind of line she would have written at the time more than me. I thought, ‘Great, let’s use that.’ I remember it being at the rehearsal studios in Camden Town. We agreed she would get an acknowledgement percentage because it was a small contribution. I didn’t know her credit wasn’t on there at first; that was probably the publisher’s decision because she contributed such a small amount to the song. Dammers/Dakar looks like it was a completely co-written song. It’s misleading. But I didn’t particularly care that much, but maybe I should have; I just think everyone knows I wrote the song.

ROGER CHARLERY: I’d known about Nelson Mandela and apartheid from school and through the Socialist Workers Party. Jerry called me and said, ‘I’m doing this thing called “(Free) Nelson Mandela” and I’d like you and Dave on it.’ We were recording at Air Studios so we took an afternoon off. Elvis Costello was producing but it was really Jerry calling the shots.

HORACE PANTER: They were recording in Air Studio 2 and I was in Studio 1 recording All the Rage with Roger and Dave’s new band, General Public. I was invited in but Brad was really off with me.

LYNVAL GOLDING: It was George Martin’s studio right by Oxford Circus. Me, Roger, and Dave did part of the backing vocals when the track was nearly finished. And then the a Capella intro was done later which Elvis arranged and chopped onto the front: when those three girls sing free, free, free Nelson Mandela it just hit you; the emotion in those voices.

DAVE WAKELING: Elvis played me and Roger the track and they’d already got every harmony going. At the time I was very keen on Prince Nico Mbarga’s Sweet Mother highlife album so I thought, ‘There’s no way you’re going to rise above the crowd here. Why don’t I go up into the range where the women are singing free Nelson Mandela and it will stand out?’ Elvis loved it and I double tracked the part. The single came out and I heard it on the radio and my harmony was really loud and I thought, ‘What a great idea.’ Then I listened to the record more and I was like, ‘Hang on a minute, that’s not my voice that’s bleedin’ Elvis Costello.’ He liked the harmony so much he sang it too. We got to do it on the Tube with the Special AKA and I was looking at him sideways, ‘Ah, singing the same harmony, Declan.’

I said to Jerry, quite seriously, ‘You ought to do a twelve inch record with a free Nelson Mandela doll in his prison uniform, like a Ken and Barbie doll. It’ll go to number one.’ Jerry was all offended and said, ‘It’s not a laughing matter, Dave.’

JERRY DAMMERS: There were these two enormously influential record pluggers called Ferret ‘n’ Spanner who were big Specials fans and they pushed the track at Radio 1. It became an international hit and went to number one in New Zealand. And it got played inside South Africa at football stadiums which was the only place black people were allowed to gather. I heard it on the news at a United Democratic Front rally and couldn’t believe it. And then Eric Honecker invited the Special AKA to East Germany because the Communist Party adopted ‘Nelson Mandela’ as their anthem. We were meant to be an example to young people of what pop music should be, which was incredible, but we didn’t go.

PETER HAIN: It’s since come to light that Thatcher wrote in a letter to the President of South Africa, P W Botha, in October 1985, ‘I continue to believe, as I have said to you before, that the release of Nelson Mandela would have more impact than almost any single action you could undertake.’ Intelligence would have told her, ‘You’re going to have to do something because this is going to explode.’ The game was up.

NEIL KINNOCK: I will bet you that the Foreign Office drafted that letter. And there would have been a hell of an argument over keeping that phrase in. This was around the time that Thatcher said, ‘Mandela is little better than a terrorist.’ She thought I was taking my orders directly from the ANC.

Gough Whitlam, the former Prime Minister of Australia, headed the Commonwealth Eminent Persons Group which did an investigation into apartheid in South Africa and whether the sanctions boycott should be relaxed. The report basically said, ‘If anything we’ve got to tighten it because these people are a bloody disgrace.’ In a press conference after, Mrs Thatcher said, ‘If it’s one against forty-eight I feel sorry for the forty eight.’ I spoke in the House and said, ‘Here’s the whole Commonwealth taking one view and a Prime Minister shamefully taking a different view and defending South Africa.’ It was that hubris that brought her down in the end. Damm and blast her! If she’d have stuck around we would have won the ’92 election.

CLARE SHORT: She was a rude ignorant woman. I don’t think she was writing to Botha out of a quest for justice. She had already stated, ‘The ANC is a typical terrorist organization.’ She would have been surrounded by people saying, ‘South Africa is dangerous. It’s going to end in bloodshed.’ So even though she was sympathetic to the apartheid regime fundamentally she would think, ‘This needs a political solution otherwise it’s going to affect us all.’ There was already war in Angola and Mozambique and the Russians were involved. And, of course, there were economic interests between Britain and South Africa.

ANGELA EAGLE: I went back to my old secondary school and one of the teachers reminded me of how somebody from Barclays Bank had come to talk about a career in banking in front of an assembly of sixth formers and how I had tackled him about their forty per cent control of banking in South Africa and he had walked out. I had an account at Barclays with a penny in it to cost them money.

JERRY DAMMERS: Thatcher got credit for telling Botha to release Mandela. Of course that was good but what had she done for the previous quarter century? You’d have had to be Adolf Hitler not to have asked Botha to do something by that time. I like to think my song might even have helped keep the pressure on her to take action by making it obvious this was becoming a very popular issue. Thatcher’s motives were different. I don’t think she necessarily wanted Mandela to become president she wanted to diffuse the situation in South Africa; and if he did become president, she wanted to be able to have influence by saying she’d supported him. She knew something had to give and the sanctions campaign tipped the balance. And all those people who didn’t bank at Barclays or buy South African fruit helped bring about change. It was people power around the world. Apparently, someone researched Hansard and from when Mandela was put in prison to the concert at Alexandra Palace he was never once mentioned in the Commons. So the hypocrisy of them all clambering on the bandwagon after the event was incredible.

CLARE SHORT: Mandela was the most honoured guest that Westminster can have in July 1996. They put the red carpet down and page boys dressed with trumpets and flags. The point being everybody wanted to be there. Tory MPs were scrambling over the chairs to get in the photographs. I believe that big historical change comes from outside and underneath. I was an activist and I would go to the demonstrations outside the South African Embassy and go on marches. I was seeing it as a broad movement of opposition. And then of course, the Mandela concerts were the apogee. It took the whole campaign into the mainstream.

PAUL HEATON: The tragedy was many years later when Mandela came over here the Spice Girls were there and Jerry Dammers wasn’t.

Except where acknowledged all of the content on this page is copyrighted and subject to reproduction law. Content may not be used, in any form, without the express approval of the copyright holder. ©Daniel Rachel 2016